Sermons

-

The Good Shepherd Is the End of Violence – The Rev. Michelle Meech

April 21, 2024

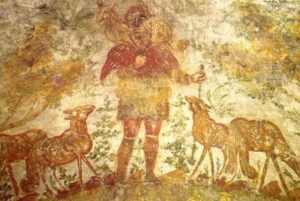

Christ the Good Shepherd – The Domatilla Catacombs, Rome

The image we have on the front of today’s bulletin is thought to be one of the earliest images of Christ we have remaining. The image of a dark-skinned Jesus in the middle of a flock of sheep, a staff in his left hand. He’s carrying one of the sheep on his shoulders, with his right hand grasping their legs. It’s an unsophisticated painting and has faded and crumbled a bit so it’s hard to make out all the detail. It can be found on the walls of the Domitilla Family Catacombs in Rome and has been dated to the second century of the common era.

It’s worth noting that this is not the only early image of the good shepherd we have, there are several. It’s also worth noting that there are no images we have that date earlier than these. It seems that early Christians understood Christ, the anointed one of God, as the Good Shepherd.

Not Christ the king who reigns in glory. Not Christ the crucified or the risen Christ. Early Christians understood Christ as the Good Shepherd. A short history lesson provides us with some context and thus, some understanding.

In the first 2 centuries after Jesus died, those who believed Jesus to be the Messiah came from both Jewish and non-Jewish backgrounds. However, this was still a small group of people and, therefore, not a significant threat to the larger Roman Empire. But there were sporadic persecutions, some by the Roman government and some by local governors. Of course, this meant that Christians were not safe. This dynamic would not shift for over 200 years, until the year 324 when Constantine made Christianity the religion of the Roman Empire. From that point on, Christianity has always been associated with worldly power and shifted its understanding of Christ to be one of worldly victor.

But back to the 100s and 200s: In response to persecutions, Christians met in secret and learned to be skeptical of newcomers to the faith. Entering a Christian community, then, meant a long period of catechism or teaching before individuals were allowed to receive Eucharist. In this context, Christ the Savior could not be equated with someone who had worldly power like a king or an emperor or a priest. It made no sense. Their savior had to be someone who would keep them safe, someone whose voice they knew and trusted. But why a shepherd?

Some of this obviously comes from scripture and the use of the metaphor of a shepherd. But that’s not the only metaphor that is used. Also, keep in mind that literacy was extremely low and people did not have access to the written word. So, again, we look at context.

Animal sacrifices were common in Ancient Rome. Pigs, ox, and of course, sheep were the most popular. The ritual of sacrifice took place in an area that needed to be purified. The animal, which they would call a victim, would be carried around the space and then killed in some ritually appropriate way, the flesh of the victim was placed on a fire, and then wine and incense were thrown upon it.

Persecutions of human beings were seen as a similar kind of event – a cleansing, a purification. A victim or victims, were sacrificed to keep the population “pure.” The good shepherd, then, was the one who kept the sheep or the victim safe, the one whose voice they knew and could be trusted. It was a code for early Christians so that they knew they were among friends.

So, what are we doing as Christians? When I talk to non-Christians about the Christian faith, this concept of sacrifice is brought up sometimes. How can we celebrate the sacrifice of a human being? How can this be God’s will? If it is God’s will that Jesus died, then the God we worship must not be a loving God. I agree.

Rene Girard, a 20th century philosopher and theologian, studied human nature and how conflict erupts in community. He developed a theory about the scapegoat mechanism in which a group in conflict seeks cohesion by blaming a person or persons for the group’s pain and suffering – a scapegoat. A desire for violence develops and once the scapegoat is sacrificed, the group has, for a time, a sense of communal peace. The problem, of course, is that the individuals in the group are unable and unwilling to engage in self-reflection to understand their part in the conflict. So, conflict occurs over and over again. Thus, the desire for violence occurs over and over again.

You can see this happening in groups all the time. It’s often called throwing someone under the bus. In order to escape the threat of suspicion and, therefore, expulsion… a kind of death… we look for somewhere else we can lay the blame. It happens in just about every human community, everywhere across the world.

This is what happened to Jesus. But this is not what we celebrate as Christians.

Instead, we see Jesus as the one who did not participate in this death-dealing ritual because he did not seek retribution for the violence. He does not choose power. He chooses love. And in his some of his last words, he offers us one of the greatest teachings of all: “Father forgive them; for they know not what they do.”

James Alison, a theologian who has studied Girard expands this theory and helps us to see more clearly what God is doing in Christ. He says: “For God there are no “outsiders”, which means that any mechanism for the creation of “outsiders” is automatically and simply a mechanism of human violence, and that’s that.”

It is the fear of death that leads humans to maintaining group peace and solidarity by excluding odd or inconvenient “others” on the false assumption that their death is the basic means for achieving peace and cohesion. The revelation unfolding in the Scriptures challenges such a common belief that God wants to punish evildoers, and this punishment takes the form of human exclusion and violence.

Jesus’ mind was formed not by rivalry and the need for victory over others, but by the complete trust in the vivaciousness of God. And the Gospels are the written witnesses of the disciples getting to understand Jesus’ mind as they – following Jesus’ death and resurrection – were looking back with the transformed ability to see either the vivaciousness of God or the satanic lie that violence is necessary for survival and peace.

This is what early Christians understood. Christ is the Good Shepherd. The one who challenges the lie that violence – that is, expulsion or death of any kind – is necessary for survival and peace. The Good Shepherd is the one who calls everyone to the Table – every single one.

The Table is where we learn what it means to accept grace and forgiveness. To let ourselves off the hook of our brutal self-judgment and become forgiven forgivers. Where we are fed by the nourishment of self-giving to become self-giving. Where we truly come to know that there is no death in God, no judgment in God. There is only love and the life offered by that love.

This is a truly subversive idea. Especially in a society like ours that is so deeply divided. In a society where the members have become self-righteous enough to think the violence always comes from the other side. But whenever we draw a line in the sand, Jesus is always on the other side. Every time.

What we learn at this Table is that nothing can break the love of God. The abundance of God’s love poured upon us is an ever-flowing stream. It never ends because there is no death in God. So we are fed from this Table in order to gain the strength to forgive ourselves for the ways we believe we don’t measure up. So that we, from this place, can offer compassion to others when they are struggling instead of believing that they are an object in our world whose purpose is to make us feel better about ourselves. So that we can walk with ourselves in the valley of the shadow of death and learn to walk with others, knowing that our Good Shepherd, the Christ, is always there ready to carry us when we cannot walk on our own.

And we are talking about real life here, our physical lives. The Good Shepherd is much more than a metaphor for a spiritual experience. The Good Shepherd is carrying the many many many people who are oppressed by the greed of the few. Low wage jobs, sky rocketing housing prices, lack of health care, environmental destruction, racism, for-profit prisons, men regulating the bodies of women, and most of that masquerading as Christianity except it’s not. It’s white Christian nationalism.

When the world draws a line in the sand, the Good Shepherd is always on the other side, gathering the sheep, reminding them of God’s love in a world that desires violence and control brought on by the need for power. The Good Shepherd is always with the vulnerable and the marginalized because God’s dream is one that overturns worldly power.

Jesus came to teach us that the worldly violence of “othering” is not of God. He offered himself to be the victim who does not seek retribution. And in so doing, teaches us what eternal life actually is. Eternal life is an end to violence. The violence we do to others. And the violence we do to ourselves.

This Easter Season, as we continue understanding Resurrection in our walk with Christ, let us remember that, first and foremost, renewal comes in the sure knowledge that the Eucharistic feast is one to which we are all invited to receive grace upon grace upon grace. Every Sunday morning, this Table is an open Table. God’s Holy Spirit works in each one of us and the life and the love offered here are available to all who choose to come, to all who feel called to come, for whatever reason.

For God’s love is freely given so that we may come to know that we are loved with wild abandon. Come to the Table today and feast on God’s love. All are welcome at God’s Table.