Sermons

-

On History and Being Known – The Rev. Michelle Meech

March 12, 2023

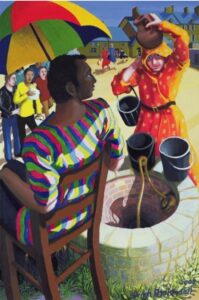

Jesus and the Samaritan Woman at the Well (2002) by Dinah Roe Kendall

Right away, we can tell that today’s Gospel story is one that speaks to the context of any two groups who have become so diametrically opposed that they cannot find common ground and seem to go out of their way to disagree with the other. More to the point, two groups of people who have, over time, developed hostility, distrust, and outright hate towards one another. A long-time conflict in which there have been so many offenses thrown at the other. In that “other group,” we always find our scapegoat, the one who will take the blame for us in our own story of ourselves.

That is what we read into this text – that there is some kind of conflict between the Jews and the Samaritans. We know this, not only from this story but also from the story of the Good Samaritan in our Gospels.

I find this fascinating that we always seem to want to know the history. Because I think, what we’re trying to do when we ask “what happened?” is decide whose side we want to be on based, of course, on our own story.

I have no problem with learning history. My history class in high school used to have this saying on the front above the black boards: Those who do not study history are doomed to repeat it. I believe that. The struggle is that we don’t always know all of the history.

For example: Most of us still do not know the full story of the Holocaust. We don’t know how complicit our nation was in the rise of extremist anti-semitism. We would rather blame it on the Nazi’s, finding our scapegoat in “the other.” I’m not saying that the Nazi’s were not evil incarnate. But I do ask you to take some time to learn more about US complicity by watching the Ken Burns 3-part series, the US and the Holocaust. It’s hard to view.

Because we would rather not know this.

Instead: It was their fault, we say. We have vanquished evil, we say. We are righteous, we say.So let’s look at this history between Samaria and Israel. For this story, we have to go back before the founding of the nation of Israel and the eventual split of Israel into the two kingdoms… although all of this plays into it.

All the way back to Abraham whose stories were told by the 12 tribes of Israel and were written down in the book of Genesis. The stories that tell us God promised the land of Canaan to Abraham and his descendants. It’s the story of the promised land, the place that Moses leads the Israelites to, through the desert wilderness from their slavery in Egypt. The place that Joshua crossed the Jordan into and conquered Jericho. This land is where Canaan was. And it came to be known as Samaria.

This land and its people who were not killed in the invasion, were absorbed into the 12 tribes of Israel, becoming the responsibility of the Tribe of Joseph, Joseph being a son of Jacob. So, this place, this whole area called Samaria, is the well of Jacob, a metaphorical description here in this Gospel reading, for the descendants of Jacob, who… let’s face it… committed atrocities in order to obtain the land.

This is where the Gospel story begins – Jesus visiting Jacob’s well in Sychar – the descendants of Jacob. This helps us understand the place a bit. By why the animosity toward the people who live there? Shouldn’t they be revered by the Jews? Samaria should be a place of honor.

And we arrive at the story we’ve heard before. The same story that defines so much of the narrative in the Hebrew Scriptures: The 12 tribes of Israel desired a king so that they could become as powerful as the neighboring nations. And, as we know, the Nation of Israel lasted through the 3 reigns of Saul, David, and Solomon before it split over power plays, into the 2 kingdoms – the Southern Kingdom, known as Judea whose capital city was Jerusalem. And the Northern Kingdom, who kept the name Israel, and built the city of Samaria in this region called Samaria. This is when they started to become known as Samaritans.

Now, imagine that when the Northern Kingdom eventually fell to the Assyrians and they sent Jewish people into exile, that the Jewish people who were allowed to stay behind in Samaria were no longer able to practice as Jews in the same way, if at all. Meanwhile, the Jews who had been exiled came to know themselves as separate from their homeland. It’s not like they had email or even regular mail that would be delivered.

Exiling people is an act of war whose specific goal is to destroy a nation. And that it did. Because finally, when the exile was over several generations later, the Jews who had been exiled knew themselves in one way and the Jews who remained in Samaria knew themselves another way. And they no longer saw themselves in one another.

Over centuries and centuries, generation after generation after generation, the Jewish people who lived in and around Jerusalem, and the Jewish people who were exiled from their land, simply came to know knew these people in Samaria as “not us.” And, therefore, untrustworthy. Worthy only of whatever hostility and violence is hurled in their direction. Scapegoats, in many ways.

Of what significance is this to the story of Jesus? Well, first, he was a Jew. So he grew up hearing stories about the Samaritans and I’m sure they were not nice stories. And the land is important. The land around the city of Samaria, that came to be known as Samaria, is between Judea on the south where Jerusalem is, and Galilee on the north, where we know Jesus is from. In order to go from one place to the other, you have to go through it.

In this particular case, Jesus was going from Judea in the south, so if he didn’t go through Samaria, he would have had to cross the Jordan River, which runs from north to south, go through non-Jewish territory on the eastern side, and cross back over the Jordan to get to Galilee. The disciples who were with Jesus, must have thought it similar to how we use the term “the bad side of town.”… don’t get me started on that phrase. For that matter, Jesus may have thought that too. He was, after all, raised as a Jew.

And, as they stop for supplies on their travels through this place, Jesus finds himself face to face with “the other.” Not just a Samaritan, but a woman.

Now, John’s writing is full of symbolism and metaphor. We have the man and the woman meeting at the well, which symbolizes courtship. We have the time of the day as noon, the time in which Jesus was hung on the cross. We have Jesus asking for a drink, and the only other time he asks for a drink is when he’s hanging on the cross. And we have reference after reference to the Hebrew Scriptures – “living water” as found in the book of Numbers. The phrase “everyone who drinks” references Wisdom as found in the book of Sirach. Worship on the mountain as referenced in 2 Maccabees. And the phrase “salvation is from the Jews” references Deuteronomy, 1 Kings, and the prophet Isaiah.

All of this to let us know just how powerful this moment is. All of these things are coming to bear in this encounter, this flashpoint in the Gospels. All things point to this.

And we are not let down. Because it is here… in this bad part of town with this woman who is known as untrustworthy… at this place that symbolizes the common ancestry of both of these people… it is here that Jesus finally dares to speak his truth aloud, it is in this moment that he gives it breath, gives it life: “I am he, the one who is speaking to you.”

I am the messiah, Jesus admits. This is the first time in John’s Gospel that Jesus entrusts this knowledge to another.

But that bombshell is not the end of the story. The disciples come back and chastise him. The woman runs off to tell everyone she meets – “Come and see the one I just met! Could he be the Messiah?” Meanwhile, the disciples insist that he must be hungry because surely, he wouldn’t have eaten with the Samaritans. And they talk about the harvest, another metaphor… this one, for those who are being saved just in the nick of time.

The layers of this story are astounding. The history, the symbolism, the references to scripture and to the coming apocalypse. It’s hard to know where to focus and what it all means.

Life is like that. It’s hard to know what will save us when we are looking for salvation in so many different ways – salvation from our own personal history, from our own emotional patterns, from our own anxious thoughts. Whenever we meet someone, all of this is happening… our history, all of the symbols we have come to rely on that tell us who this person is, the references to what has formed us and our imaginations, wondering what will become of us in the future.

It’s all happening in all of our encounters all at once – if not consciously then unconsciously as tensions carried in our bodies and emotional patterns carried in our amygdala.

And yet, what we see here, essentially, is that in this one meeting both of these people are changed forever. Jesus, somehow, sees this woman as exactly who she is. Maybe for the first time in her life. And she is renewed by that. And Jesus claims his true identity for the first time. He had been in Jerusalem, as a matter of fact, where people saw the signs he performed and believed in him but he did not entrust himself to them. He hadn’t told his disciples either.

Somehow, for some reason, this is the place. In this intimate moment with a stranger who is not so strange, there is permission to be real. To be seen. To be known.

And I don’t know the reason why it was that woman or that place or that moment. It could have been any one of the dozens of layers that John laid down on top of this story about this single encounter. And I bet we all have a different take on what that reason might be.

But what I do know is that it means something to be known. It means something to be truly seen for who we really are – sins and foibles and all. It means the world to us when we are able to really see ourselves in another. We drop in and stop the dance of history and emotional patterns and opinions and judgments and worries. And we realize that we are ok. That even we, are beloved of God. Nothing to prove. Nothing to defend. Nothing to grasp.

Christ comes to meet us in this most vulnerable place and makes Christself known to us. Letting us know the battle is over. We have been found. We are known.

If we pull back from the intimacy of this meeting, we can see how this all fits with the bigger picture of God’s justice in the world. In order to do the work that we are called to do as disciples, if we want to change the world and right the wrongs and vanquish the evil, we have to meet Christ in a real way. We have to bring all of ourselves, the things we love about ourselves and the things we hope no one ever finds out about us. All of ourselves, we have to bring to Christ’s light.

Otherwise, we are beholden to all of the other things – our history, our emotional patterns locked in our amygdala, our anxieties and worries about the future, our body’s tensions left over from the trauma in our lives. In being beholden to those, we are only ever going to look for salvation from our own story. Even the ministry we do in the world, becomes nothing more than an attempt to win our own salvation.

Our thirst may be quenched for a minute. But we will always be thirsty again… and again and again.

Like our national story about the Holocaust:

It was their fault, we say. We have vanquished evil, we say. We are righteous, we say.Like the stories we sometimes tell ourselves about why it’s ok for us to act out:

They made us do it, we say. We have to protect ourselves, we say. We are righteous, we say.But the water that Christ has for us is living water. Water that becomes in us, a spring that gives and gives and gives. And we never become thirsty again because we know who we are. We accept who we are. We love who we are, having become known fully by Christ.

The Samaritan woman met Christ and was known by Christ. And it changed her forever.

As your priest, I beseech you: be known by Christ. Come and drink of the living water, my beloveds. And learn what it means to Love, truly love, as God loves us.