Sermons

-

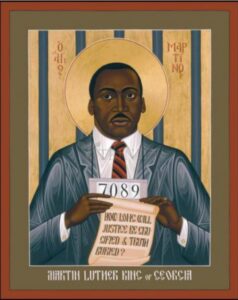

In honor of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr…. Beloved Community: Come and See – The Rev. Michelle Meech

January 15, 2023

Words from the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.:

Several months ago, the [Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights] affiliate here in Birmingham asked us to be on call to engage in a nonviolent direct action program if such were deemed necessary. We readily consented, and [are] here because [we were] invited here. I am here because I have organizational ties here.But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here. Just as the prophets of the eighth century B.C. left their villages and carried their “thus saith the Lord” far beyond the boundaries of their home towns, and just as the Apostle Paul left his village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to the far corners of the Greco Roman world, so am I compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my own home town…

Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly… – from Letter from a Birmingham Jail

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King wrote this in his jail cell on an April day in 1963. Nearly 60 years ago. Dr. King wrote this nearly 7000-word letter by hand to white clergy leaders in the city of Birmingham AL because they had publicly criticized his presence and activities there calling them “unwise and untimely.”

Martin Luther King Jr. was born in 1929 and raised in Georgia by a Baptist minister – his father, Martin Luther King Sr. Growing up, scripture was read regularly in his house as you might imagine. In his teen years, however, young Martin grew to have doubts about the religion in which he was raised. The trouble mostly being with the church itself, finding those who worshipped more concerned with displays of emotion than with life itself as lived in the here and now.

So, when he finally found in Jesus, the extremist for Love, as King called him in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” Rev. King knew his own path of service was born directly from the Gospel. He found that the liberation proclaimed by the prophets and promised by Jesus himself, not a vague, formless spiritual sense of peace… but something real and tangible.

The Rev. Dr. King understood Jesus as someone who stood against the tyranny of unjust laws. Who stood against evil systems. Someone who was willing to give his very life in order for the world and its unjust systems to be overturned. In his work for societal change, the Rev. Dor. King had learned about the principles of non-violent protest from Mahatma Gandhi and Thich Nhat Hanh. He came to equate these with the Gospel of Christ.

Jesus’ desire was not to defeat those who disagreed with him in armed conflict as some of his followers had hoped, but to continue speaking the truth in non-violent ways until those who were not able to see through the dimness of their own small, self-centered view of the world, can finally be reached by God’s light in order that all may live as members of the Beloved Community.

I have a dream today!… the Rev. Dr. King said later that same year – 1963 – on a hot August day in Washington DC… I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight; “and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.”2 – from “I Have a Dream”

These words from the prophet Isaiah are often used in Christianity to describe the coming of Christ, the incarnation of Love itself, the reclamation of justice in the world that is yearned for when hills and mountains and rough places have been fabricated and erected from the greed and arrogance of those who crave power and who guard their ground jealously.

In today’s Gospel when John the Baptist declares Jesus to be “the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world”… this isn’t a “just accept Jesus into your heart and all will be forgiven” kind of declaration that we hear from a different strain of Christianity in our country.

Our Gospeler John is referencing the sacrificial Passover Lamb described in the book of Exodus, chapter 12 – the blood of which was used to signify who God’s people were. Those who ate of the lamb and marked their homes with its blood were members of Israel and were to be spared. It has come to be called the Passover because God will pass over those houses that are marked, and will enact punishment and judgment on those houses that are not marked.

In a similar way, Jesus became that signifier for those who followed him. Jesus has become for us, a path of salvation – not just by saying we believe in him – but by truly believing in him as we continue to empty ourselves in our work to remove the hills and mountains and rough places. By believing in the power of Love – for which Jesus was an extremist – by believing in the power of Love so profoundly that we are willing to stand for the sake of Love itself in the face of evil and all of its disguises – racism, classism, homophobia, sexism, ableism, ageism – the many ways in which we try to insist that one group of people has more rights than another and, therefore, cannot see past how they have constructed society to cater to their own perspectives and biological realities.

Dr. King saw the connections in American society. How racism and poverty were deeply connected. How war, as evidenced by the Vietnam war, had become for the moguls and power base of America. More about making money than it was about the necessity of vanquishing evil. And that most of the people who were forced to fight by way of the draft were poor people and people of color, while corporations and the military industrial complex grew bigger and more powerful.

Dr. King decided that peace and anti-poverty had to be an integral part of his fight for Civil Rights. He offered these words to a full house at Riverside Baptist Church in NYC on April 4, 1967, a year to the day before he was assassinated.

As I have walked among the desperate, rejected, and angry young men, I have told them that Molotov cocktails and rifles would not solve their problems. I have tried to offer them my deepest compassion while maintaining my conviction that social change comes most meaningfully through nonviolent action. But they ask — and rightly so — what about Vietnam? They ask if our own nation wasn’t using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted. Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today — my own government. For the sake of those boys, for the sake of this government, for the sake of the hundreds of thousands trembling under our violence, I cannot be silent. …

And he spoke about his “commitment to the ministry of Jesus Christ…” saying: “To me the relationship of this ministry to the making of peace is so obvious that I sometimes marvel at those who ask me why I’m speaking against the war. Could it be that they do not know that the good news was meant for all [people] – for Communist and capitalist, for their children and ours, for black and for white, for revolutionary and conservative? Have they forgotten that my ministry is in obedience to the One who loved his enemies so fully that he died for them? What then can I say to the Vietcong or to Castro or to Mao as a faithful minister of this One? Can I threaten them with death or must I not share with them my life?

… I must be true to my conviction that I share with all [people] the calling to be a son of the living God. Beyond the calling of race or nation or creed is this vocation of sonship and brotherhood, and because I believe that the Father is deeply concerned especially for his suffering and helpless and outcast children, I come tonight to speak for them.

This I believe to be the privilege and the burden of all of us who deem ourselves bound by allegiances and loyalties which are broader and deeper than nationalism and which go beyond our nation’s self-defined goals and positions. We are called to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation and for those it calls “enemy,” for no document from human hands can make these humans any less our brothers. – from “Beyond Vietnam – A Time to Break Silence”

Throughout his leadership of the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th Century, the Rev. Dr. King was nourished by an image, an idea, a concept he had learned as a member of an early 20th century organization called the Fellowship of Reconciliation. Something called Beloved Community.

Not to be confused with the Biblical image of the “peaceable kingdom” in which the lions and lambs coexist in some kind of idealized blissful accord that is unobtainable, the Beloved Community is an enfleshed, corporeal peace. A peace that is possible when a critical mass of people make a solemn commitment to non-violence.

Not just refusing to hit back when struck, which is a twisted version of Jesus’ turning the other cheek, non-violence is a path in which we learn how all privilege and power we have are ultimately a part of a larger violent system that forces us to protect whatever ground or power or stuff we think belongs to us. This violent system causes us to think selfishly instead of communally so that we hoard instead of share. We lock the door instead of inviting everybody in. We try to keep things the same, worried about what we won’t have any longer, instead of opening to who we are being called to become.

The image of the Beloved Community, on the other hand, opens us to the very real possibility of living into our call to truly become the Body of Christ in and for the world.

As King said, “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” (see above)

We are these points of light on a web – like Indra’s web that I described last week – and the truth is inescapable, we are one another’s keepers because what happens to you, happens to me. The privileges that one does not have become owned by the ones that do have them. And none of us is truly free until we are all free.

The practice of non-violence is understanding this interconnectedness so that we seek to prevent violence of any kind – the violence of low wage or no wage sweat shops that make cheap clothing in Asia, the violence against poorly treated animals that become our food, as well as the violence of war and physical harm itself. And the violence we visit upon ourselves in our own self-judgment.

Perhaps, most importantly right now, the path of non-violence, the path toward Beloved Community, is one of racial reconciliation which includes truth-telling and confession, the proclamation of hope, participation in formation and practice, and a commitment to justice work that repairs the breach in our society and institutions.

Our Gospeler John gives us an intriguing and mysterious narrative in today’s passage. After John the Baptist introduces Jesus as the one through whom salvation is found, John’s disciples start following Jesus. And when Jesus asks them, “What are you looking for?”, they respond: “Rabbi, where are you staying?”

We might think that the disciples are asking about his lodging but that’s not accurate. Where are you staying means… what are you about, where do you reside, where do you live… Where is your heart?

And Jesus’ reply: “Come and see.” Jesus doesn’t come home with us, he invites us to come with him. Following Jesus then requires us to give up where we live, where we are staying, where we prefer to spend our time. Following Jesus asks us to become what God would have us become. To reside, not in our troubles and longings, our fears and desires generated by the world and its inequity, but to reside with him by seeing through the dim landscape into the brightness of God’s light on the path toward becoming beloved community.

Come and see, Jesus says. Come and see.

Come and see the possibility of God’s Love in this world.

Come and see the hope of God’s light in all of us.

Come and see the brilliance of God’s heart beating through you and through me.

Come and see how good this can really be.The Rev. Dr. King said this:

… the end is reconciliation; the end is redemption; the end is the creation of a beloved community. It is this type of spirit and this type of love that can transform opposers into friends. It is this kind of understanding good will that will transform the deep gloom of the old age into the exuberant gladness of the new age. It is this love which will bring about miracles.. – from “The Role of the Church in Facing the Nation’s Chief Moral Dilemma”